Train Station Friends

We left for Prague from Bratislava’s oldest train station which appears to have had little improvement since the Soviet era. We saw minimal English signage and no live staff.

Down the track, a middle-age woman sat on a bench and I plopped next to her. I asked if this were the train to Prague and she said confirmed it.

We struck up a conversation, or as best we could given her limited English. Her name was Marina, but not spelled anything like that because she’s Russian and I have no idea how that works. She moved to Ukraine in her 20s where she lived for 23 years. She also lived in the Czech Republic and now Bratislava.

Marina said she works for a group that helps Ukrainian children. I imagine it has something to do with the war but the question hovered beyond our language capabilities. Later I looked at a map of Slovakia and noticed it borders Ukraine to the east. This is real stuff here.

Marina said she speaks Russian, Ukrainian, Slovak, and some English. She said that not many Americans visit Bratislava. She said that the people in Bratislava are known for being helpful and having good and affordable food.

At Home in Prague

I smelled it a few times out and about and it reminded me of back home. Not the conventional Oregon scents of trees or rivers or rain, but pot. Cannabis is legal here, too, same as in Slovakia and Austria. The mini-marts carry cannabis chocolates and hard liquor right next to their Fantas and Bounty bars.

Unlike a lot of European cities, pedestrians rule the streets of Prague. Drivers stop for you when they merely suspect you want to cross. If you hesitate, they wave you across.

Pot and pedestrian culture, and tons of bridges, too? So very Oregonian. Prague and Portland oughta be sister cities.

Prague Old City

Rick Steve’s book delivered us to the Tyn church on a Sunday morning where we heard a few minutes of Mass in Czech. It made me think of my devout great-grandma Aloise celebrating Mass in this very language. In eastern Oregon, the family read from Aloise’s old Czech Bible for their substitute version of Sunday services when weather prevented them from making it into town.

And who knew we’d like the Museum of Medieval Art so much? Jim took photos that may serve as inspiration for more door paintings one day, but he got gently scolded by a guide for stepping onto a divider mat. Jim constantly frets when I stand near paintings and point my fingers too closely, but he gets busted more often than I do.

Wenceslas Square

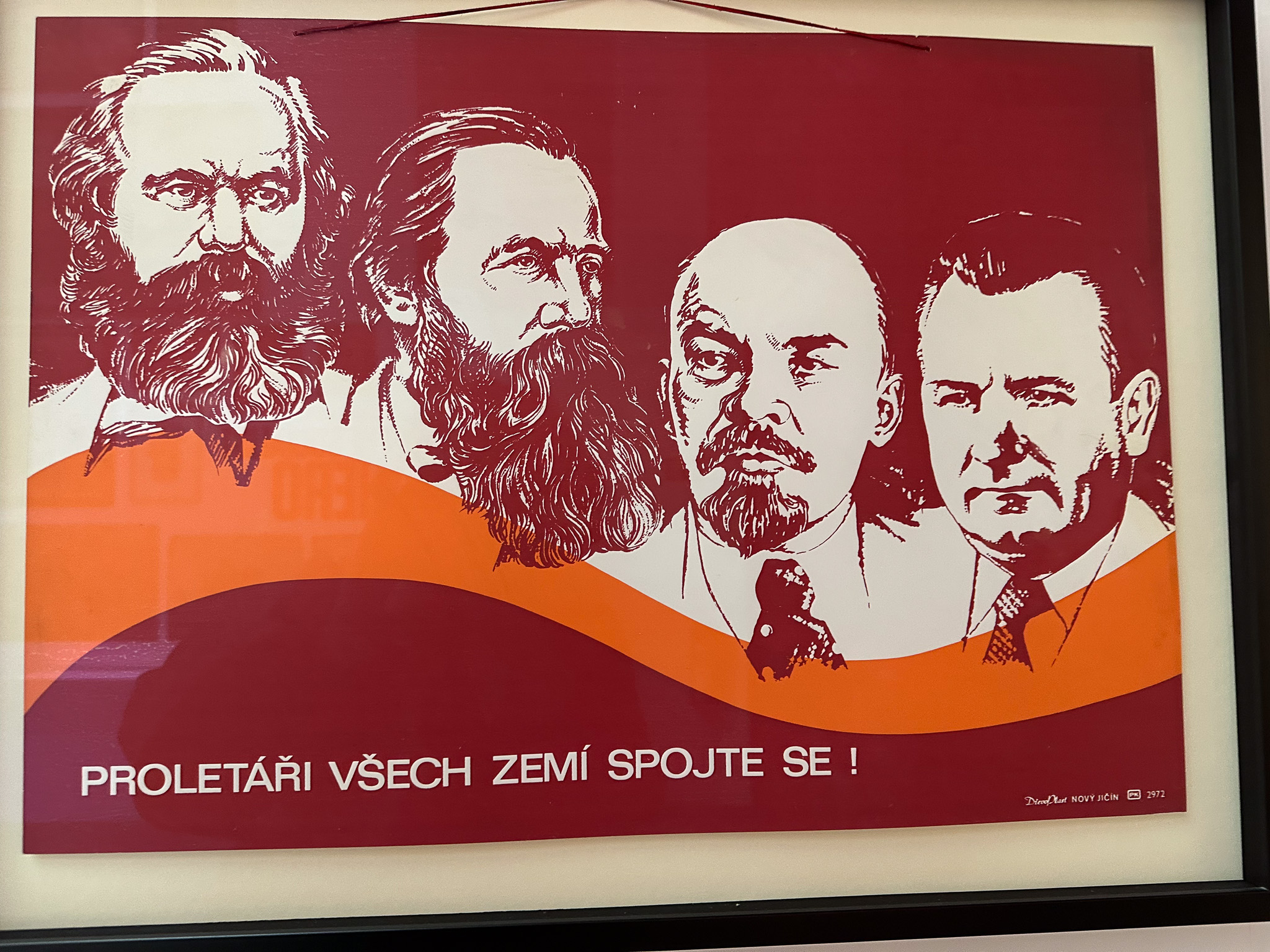

Today it’s packed with tourists, but Wenceslas Square held two of the most significant events in modern Prague’s history: the Prague Spring and the Velvet Revolution.

During the Prague Spring of 1969, my cousin Mary Kay and her husband were stationed at a US military base in Germany where he served as a dentist. They took advantage of the sudden openness in Czechoslovakia to visit Grandma Aloise’s town of Provodov. Sadly this freedom lasted only a few months before Soviet troops rolled tanks onto Wenceslas Square and squelched it all.

In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell and the USSR wobbled. Wenceslas Square once again filled with crowds. The Velvet Revolution, a largely peaceful protest, marked the end of communism in Czechoslovakia.

Soviet Bunker

We left early for our half hour walk down the hill, across the river, and through Old Town this morning. I figured we had plenty of time but a detour and getting lost made it tight for our Cold War tour on Wenceslas Square. And I had to use the bathroom pretty seriously.

We entered the Jalta Hotel at 8:50 AM where our tour meets. Surely they have some type of arrangement with the hotel about restrooms? I told the suited concierge that we’d arrived for the 9 AM tour and please did they have a restroom I could use before it starts?

“No, sorry,” answered the thugs, blank-faced. “We don’t have restrooms here. You’ll have to go next door to the Primark. They have a restroom upstairs.”

I had no clue what Primark meant but discovered it was a department store two doors down that reminded me of a JC Penny from the 1970s. We ran, barely making it back in time.

Our guide, the chipper Jacob, appeared and announced that if anyone needed to use the restroom before the tour, they could find it just through the hotel restaurant. Right there, he smiled, pointing to the left.

Jacob guided us down an elevator and a couple flights of stairs to the basement where the Soviets had created their Cold War bunker. From here they could house 150 communist leaders in the event of nuclear fallout. They also could order mid-range strikes of nuclear weapons.

We learned how during the Cold War, the Soviets carefully designed the Hotel Jalta to house visiting foreign dignitaries. They assigned western visitors the “red” guest rooms, the ones with the best bugs and phone tapping capabilities. Less interesting guests stayed in yellow or green rooms with fewer monitoring devices. Jacob showed us the control station with the map of room colors and the tapping and recording equipment.

The Soviets also targeted foreign guests with communist prostitutes, ones trained to take compromising photos which could later be used for blackmail. The prostitutes ended up amongst the highest earners in Prague. The hotel encouraged diplomats to keep their complimentary shoe brushes in hopes they’d carry them back to their embassies. The Soviets could then listen from the bugs implanted inside.

When Jacob’s father was 16, he attended an anti-Soviet assembly and thereafter was targeted and black-balled by the communists as an undesirable. They imprisoned Jacob’s dad for five years and neither he nor his children were allowed to complete school. When Jacob’s parents first began dating, communists tried to convince his mom to end their relationship, threatening that any future children could be taken away someday.

Jacob explained that communism isn’t popular in the Czech Republic today and that few youths, in particular, have any interest in it. He made a point to remind us that communism existed here only 36 years ago. “Like nothing,” he said, snapping his fingers.

He showed us where the communists stored their extra water and food supplies. For years, they would send their expiring foods to the hotel upstairs and people regularly got sick from it. But no longer, Jacob emphasized. “I eat lunch at the hotel everyday and am just fine.”

Jacob described how hard it was for people to escape the country. You needed a specific reason to travel and had to rank high up the communist ladder. You could carry only a small amount of money and never bring along any family members. This, of course, helped prevent defections. If you somehow did escape, your family back home would bear your punishment.

He showed us the rubber mallet that guards used in the interrogation room, a weapon designed to hurt but not break bones. They’d use the handle end on fingers for maximum pain. Once Jacob and fellow tour guides experimented and Jacob learned the hard way that it can break bones, revealing his disfigured finger.

All rooms in the bunker came furnished with communist-made materials except for one teletype machine from West Germany. The communists didn’t want to use it but had to because, unlike their own, this one actually worked.

Jacob explained how communist police forces recruited the most brutal of members possible. The Soviets emptied Czech prisons of their worst violent prisoners—murderers, rapists and sadists—and assigned them police positions.

Jacob discussed how over time, communism changes peoples’ ethics. “Living under totalitarianism all those many years will deform your morality,” he said.

How Did This Happen?

The following day at the Museum of Communism, we learned that the Czechs could have avoided communism had they pushed back more. Instead:

- Like many countries after WWII, Czechoslovakia was poor and vulnerable.

- People listened to Soviet propaganda.

- They suffered weak leadership who caved too much, too easily.

US Secretary of State George Marshall realized that many European nations were susceptible to the USSR after the war. He offered money for food and rebuilding if they’d agree to join America’s Marshall Plan.

Czechoslovakia’s president asked the Soviets what they thought. Could they have permission to join the Marshall Plan? Of course not, the Soviets answered. And that was that.

Terezin

Today we hired a driver named Prem to transport us to a Holocaust site north of Prague called the Terezin Memorial. Terezin had no gas chambers and served more as an early labor camp than an extermination camp. It provided poor and overcrowded conditions where Jews were more likely to perish from disease or malnutrition than execution.

Hitler packed “those with David’s Star,” as Prem called the Jewish people, into Terezin until he could figure out what to do with them. Eventually the camp operated as a way-station for Auschwitz where Nazis could gas people en masse.

Early in WWII, the Red Cross started asking questions about the conditions of Nazi concentration camps. Hitler spent a year falsely beautifying Terezin for the Red Cross’s eight hour inspection. They planted rows of flowers (removed immediately post-inspection) and installed rows of bathroom sinks (not attached to any actual plumbing) among other tricks.

The Nazi’s held a Jewish filmmaker at Terezin and made him produce a propaganda film about the camp, one which had little to do with reality. Shortly after the movie’s completion, they sent the filmmaker to a gas chamber in Auschwitz.

Prem said he sometimes drives Germans to Terezin and Auschwitz and they still feel guilty about WWII. Prem believes they shouldn’t feel personally responsible about it anymore, but he understood.

.jpg)

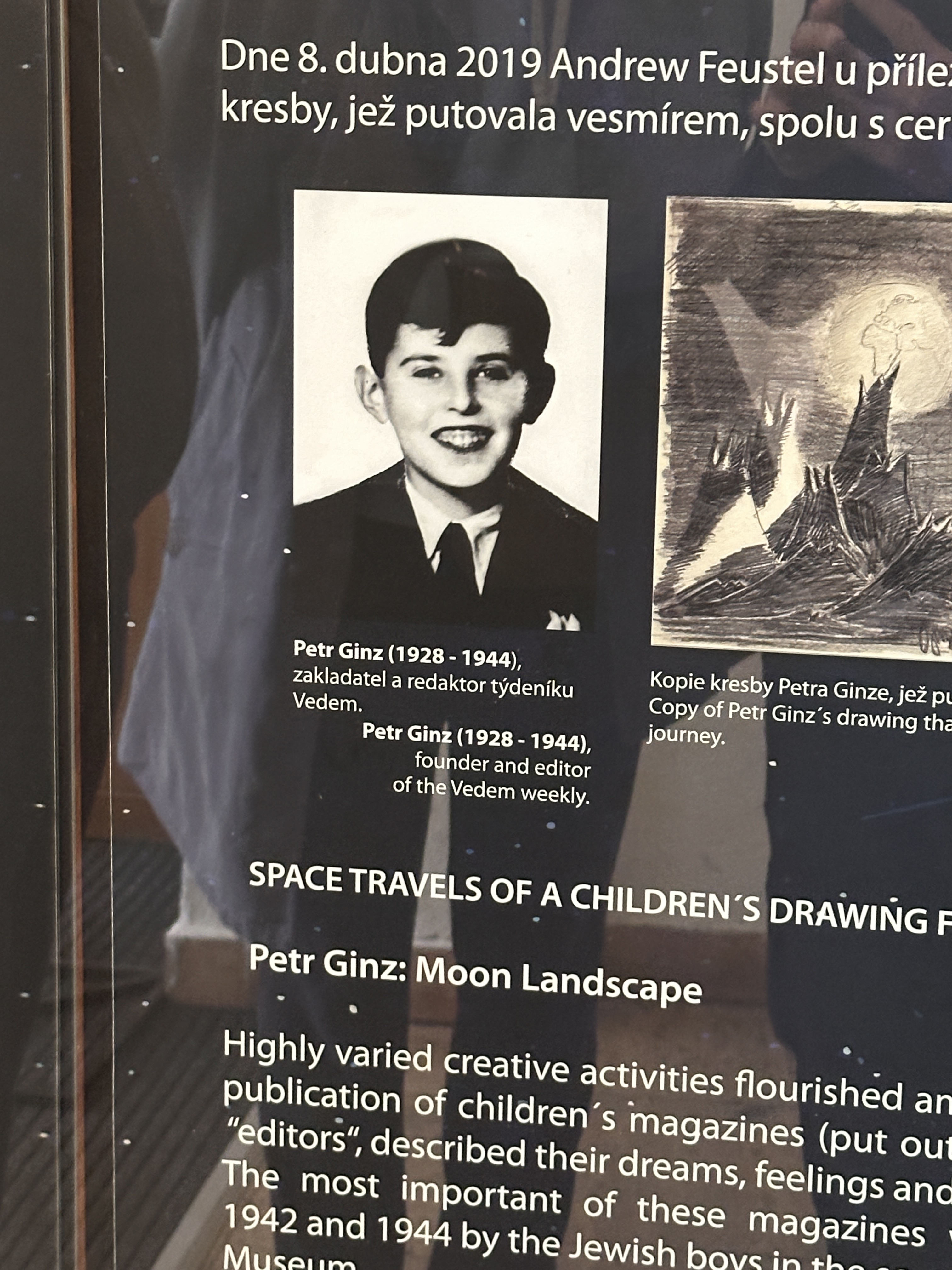

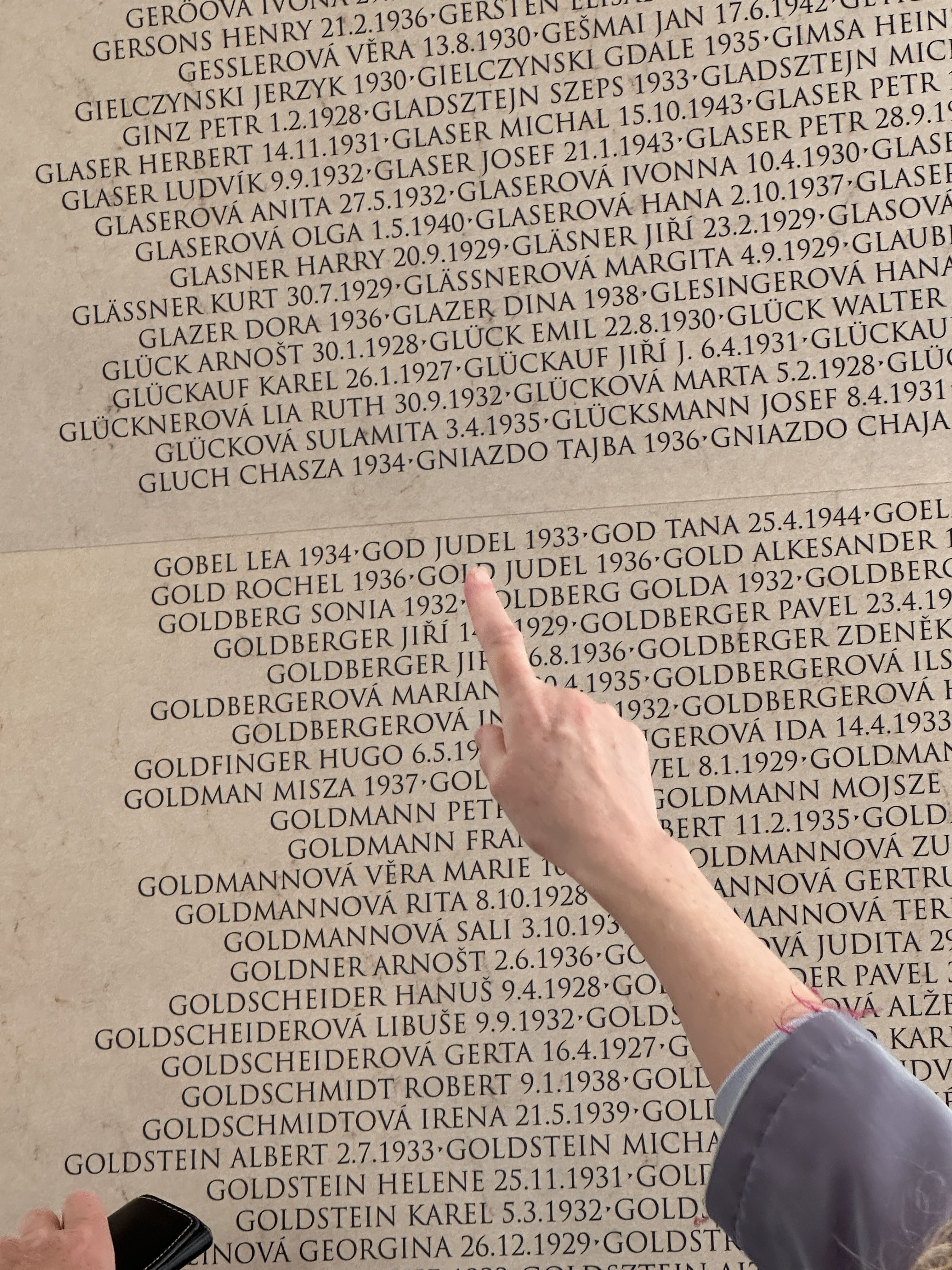

Petr Ginz

Before our trip, I read about a Jewish boy from Prague named Petr Ginz, the Terezin equivalent of Anne Frank. Petr was a boy genius, writer, diarist, and artist who got transported to Terezin at age 14 and to his gas chamber death at Auschwitz at age 16.

At Terezin, a teacher encouraged Petr to create an underground magazine with contributions from other boys in the camp. Terezin’s museum displayed some of Petr’s hand-written magazine pages as well as a few of his drawings.

Prisoners worked ten-hour days of hard labor in cramped, unsanitary settings with little food. But in the evenings, teachers among them secretly continued the children’s education as best they could.

A former art teacher had children draw as a form of mental health therapy at Terezin. She saved over 700 works in a suitcase that somehow outlasted the war. The artwork provides some of the truest documentation of the camp; Nazis normally only bothered with photos for propaganda purposes.

Jewish adults also did their best to maintain a sense of humanity and culture at Terezin. They covertly practiced their faith and shared their talents of music, drama, art, and writing, providing a glint of hope beyond the camp.

A few days later at a Prague synagogue, we encountered more drawings by Terezin children…with reminders that hardly any of them survived the war.

Old Jewish Cemetery

Prem on the Communists

Prem described communism as a “morally broke version of socialism.” He lived through communism but was just a boy during the Prague Spring. Mostly he remembers the adults in his world getting pretty worked up about it.

Prem explained how the Soviets cracked down on the Czechs during the Prague Spring, sending armies from other Warsaw Pact countries such as Bulgaria, Hungary and Poland. Afterwards the communists had a litmus test question for Czech individuals.

“Do you support international help?” they’d ask. (By this they meant, do you support the Soviets sending in these Warsaw Pact armies?)

The Soviets interviewed about a million people with this question. If you said no, you’d lose your job to a much inferior one.

Many people lost their jobs.

Working as a laborer was considered the best job during communism. They earned higher wages, and communist propaganda celebrated them as heroes. “They give you electricity for lights!”

I asked Prem why anyone would go to the trouble of studying for a professional career such as engineer or physician when everyone was paid roughly the same under communism. Prem thought it was a matter of generational pride within individual families.

I wondered what was more brutal for the average Czech—life under the Nazis or the communists? Prem said he liked the question, but it depended on when you were asking. Life was worse under the communists in the 1950s and under the Nazis from 1948-1953.

Prem decided that the absolute worst was during that era under the Nazis. They could and would destroy you for their own amusement.

Under the communists in the 1950s, if you got in trouble, you’d get a rope around your neck. In the 1970s, you’d lose your job.

Today, you rarely see any German or Russian language in the Czech Republic. I think the Czechs don’t want the reminders. The German language brings not just Nazis to mind, but Habsburg Emperors who ruled over them for centuries. The Russian language reminds them of oppression under communism. The Czechs are annoyed by tourist shops which sell Russian nesting dolls and furry Russian hats, neither of which have anything to do with them.

As in Slovakia, Prem said that Czech students had to study the Russian language during the Cold War “in honor of the fatherland.”

“Russian was compulsory until 1989,” Prem said. “Overnight it changed from Russian to English.”

As we approached our hotel, Prem pointed out the Saint Nicholas church tower. Soviets spied from there with a direct sight line to the front doors of the United States, British, or West German Embassies. They would record anyone suspected of trying to emigrate to one of these western countries.

Saint Nicholas Church

Earlier this morning we passed a long line of people outside the US embassy. Prem said it was Czechs wanting to move to the States.

Prague Palace

Today we toured the ancient Saint Vitas Cathedral and other sites on the castle grounds. Austrian Emperors ruled from here instead of Vienna from 1583 to 1611 when the Ottomans pushed too close to Vienna.

South Korean tour groups fill today’s squares. Prem told us that Prague used to have more Russian and Chinese groups, but that ended with Covid and the Ukrainian War. He said now it’s mostly South Korean and after that, Spaniards. Next come other Europeans, and finally, Americans.

We toured the Lobkowicz Palace on the castle grounds. It belonged to the noble Lobkowicz family for centuries along with their impressive collection of treasures. The family escaped to the United States right before WWII, leaving everything behind. First the Nazis grabbed it all up, then the Soviets.

In 1989, the Lobkowicz family watched news of the Velvet Revolution on their televisions with great interest. After the communists left, the Czechoslovakian government created a program where rightful owners could apply for restoration of properties. The Lobkowicz’s had only a couple of years to complete the complicated paperwork, but they succeeded.

Today they own and operate their old family palace as a museum with many of their original treasures inside, including two Canaletto paintings, a Bruegel painting, and sheet music with notations by Beethoven and Mozart.

Pilgrimage Chapel

Our favorite site of the day was the Loreta Church with its Holy House chapel. Tradition claims that one of its beam originates from Mary’s home in Nazareth. Whatever the truth, this adorable chapel has long served as the departure site for the pilgrimage of Santiago de Compostela.

.jpg)

Prague Architecture

This morning we walked across Prague’s neighborhoods and bridges to the Ginger and Fred Dancing House, a building designed by American architect Frank Gehry. As we passed example upon example of impressive architecture, I pondered the legacy of old buildings. Unusual for a European city, Prague escaped almost all wartime bombing. (The city’s penchant for stone over wood no doubt also helped with its long-term preservation.)

I’ve thought about the passing down of culture through the generations—the Bible, medical knowledge, Mozart, Michelangelo, Mr Shakespeare…

But I’d never given much consideration to the heritage of architecture, how these structures combined and survived for so many centuries to produce today’s unique amalgamation. History made it in a precise, layered way. You could never recreate it.

The Dancing House

We splurged on the fancy buffet breakfast on the 7th floor of the Dancing House. The reason to eat here?

- To rest our feet after our long walk.

- To gain access to its great views.

The hostess scurried off when we arrived then returned with a co-worker. (We figured the hostess didn’t speak English.) We arrived at 9:30 AM and the co-worker explained that the buffet (with the ’t’ pronounced) would last until 10 AM. We said that’s fine.

The buffet was good though somewhat picked over. We selected our food and beverages and got straight to eating. At 9:55 AM the waitress declared “breakfast is over!” and began clearing our plates and glasses, including unfinished ones.

We climbed the last short flight of stairs which directly connected the restaurant to the viewpoint. I handed over our breakfast receipts, assuming this would gain us entry. “Not the same place,” the attendant intoned. So we paid more for the view, and we didn’t regret it.

Czech Heroes

Afterwards we walked a couple blocks to the memorial for the Czech Republic’s greatest heroes, Josef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš. These resistors trained in Scotland and parachuted back into Prague with a huge mission: to assassinate Hitler’s second-in-command and the principal architect of the Holocaust, Reinhard Heydrich.

The Heroes!

Josef and Jan's plan didn’t go perfectly but they ultimately succeeded in taking out Heydrich. For two weeks, they hid with five other paratroopers in a crypt below Prague’s Church of Saints Cyril and Methodius.

An associate panicked and reported their location to the Nazis. The paratroopers held off a siege of 750 Nazis for two hours before taking their own lives. Today their betrayer is the Czech Republic’s greatest villain, his name a synonym for evil.

Garderobes!

Our combination ticket from the Museum of Medieval Art granted us access to other National Gallery of Art museums in Prague. We decided to visit the Sternburg and Schwarzenberg palace museums up at the castle.

After showing our tickets at the Sternburg, I study the brochure rack, hunting for one in English.

“You gotta come now!” Jim whispers, panicked. “A lady is staring at us!”

The 50-something guard with short, dark hair bee-lines over and glares at my light cloth coat. “Garderobe!” she orders, indicating the cloakroom to her right.

“I’d like to keep my coat if I could, please,” I answer.

She doesn’t like that and rattles on something more about coats in Czech.

“Sprichst du Deutsch?” she asks.

“No,” I said, understanding at least enough German to know I don’t speak it.

That’s the only German phrase I know besides:

- Ich bin ein Berliner! (I’m a Berliner!) from videos of John F Kennedy at the Berlin Wall.

- Nein, ich glaube nicht (No, I don’t think so) from hearing my older siblings practice their high school German.

But I figure neither of these statements will help matters here.

I’ve been to my share of European museums, and this is the first time somebody has tried to seize my coat.

I become a resister.

The German-speaking guard grows increasingly frustrated but eventually surrenders in exasperation. She makes some weird gestures and warnings about my coat and reluctantly waves us through, but she is far from happy.

Upstairs I learn why she wanted to confiscate my coat. The rooms are warm. (Also probably for security reasons in case I decide to snatch one of their valuables.) I remove my coat and lay it over my arm.

Seconds later, a colleague of the downstairs commandant looms at my side. She reprimands me something guttural about hauling myself and my coat back down two flights of stairs to the garderobe. I understand enough to appease her and I put my coat back on, chastened.

After that we garner suspicion in every room, trailed and traced as instigators, likely with radioed warnings to bouncers in upcoming wings. I sweat through it all and not just because of the temperature.

The paintings have descriptions in Czech, German, and then English. This is the only place in our week in Prague that I see anything written in German.

.jpg)

We still have the sister Schwarzenberg museum across the courtyard to visit. “Garderobe!” the guard there bellows at first sight of me, indicating their own coat check-in. I cave, follow orders, and surrender my coat to the cloakroom chamber.

I think about cultural remnants and generational trauma, particularly following four decades of Soviet occupation.

And that the capitalistic concept of pleasing your customer can take a while to fully sink in.

Hotel Totalitarianism

This morning when we checked out of our hotel, I reported two items to the receptionist:

- Jim ate the peanuts from the honor bar. Cost? About four dollars.

- A Prosecco goblet broke in the dishwasher.

.jpg)

The receptionist gasps with the news about the goblet. “We can’t get those anymore. I will charge you,” she informs, calmly but firmly.

Crap, I think.

I decide I need to better explain what happened with the goblet. Jim had opened the hotel’s welcome bottle of Prosecco after our arrival and poured himself a glass. I’d considered loading the provided goblet into our dishwasher but realized it could easily break there due to its length. I loaded our other dishes but left the goblet out on kitchen counter.

Neither of us could figure out how to start the dishwasher, so I left notes asking the maids to please run it for us, and they did. But yesterday when I unloaded the dishwasher, I noticed they’d included the Prosecco flute, and it had cracked and broken.

I explain this to the receptionist. Her response: “Okay, I will not charge you. I will charge the maids.”

I cringe for the maids.

Leaving Prague and More Deep Thoughts

A friendly Middle Eastern driver named Hassan transported us to the airport. Hassan tuned his radio station to US pop and I asked if Czechs enjoyed American music, remembering we heard it everywhere.

Hassan laughed and said he likes to play music according to his passengers’ nationalities. Last week he drove some Greeks to the airport and they were delighted when he played Greek songs.

Approaching the airport, I noticed that all the vehicle signage was in Czech. Nothing in English, not even for departures or arrivals lanes. Jim and I never miss driving in Europe.

We ate lunch at a traditional restaurant in the Prague Airport. Denis and Pavel were gracious middle aged waiters who took good care of us. Jim ordered a tasty sausage and I try to order the chicken.

.jpg)

“I’ll have the chicken,” I say.

“How about the salmon?” Pavel answers.

“I’ll have the salmon,” I respond. It is awesome.

When we leave, Denis asks, “Five star review?” and I return his high five. Then in one breath he says, “Thank-you-very-much-I wish-you-nice-flight-bye-bye.”

Migrating Home

Through our plane’s window I spot Oregon’s snowcapped Cascades and rolling hills, well-slathered in tall timber. But mostly I note the color green, something which still strikes me every time I fly into PDX. Not the hardened gray stone of Prague generations, but the green of Oregon’s uncorrupted spaces. And I think about how our country has never suffered foreign war or occupation on our own soil.

I’m grateful to my great-grandparents Aloise and Edward for taking a risk, for saying goodbye to their villages in Czechoslovakia, for their struggles for the greater good of our family. I’m grateful for this verdant life they left us.